14 WAYS TO ACQUIRE KNOWLEDGE

- PRACTICE

Consider the knowledge you already have — the things you really know you can do. They are the things you have done over and over; practiced them so often that they became second nature. Every normal person knows how to walk and talk. But he could never have acquired this knowledge without practice. For the young child can’t do the things that are easy to older people without first doing them over and over and over.

[…]

Most of us quit on the first or second attempt. But the man who is really going to be educated, who intends to know, is going to stay with it until it is done. Practice!

- ASK

Any normal child, at about the age of three or four, reaches the asking period, the time when that quickly developing brain is most eager for knowledge. “When?” “Where?” “How?” “What?” and “Why?” begs the child — but all too often the reply is “Keep still!” “Leave me alone!” “Don’t be a pest!”

Those first bitter refusals to our honest questions of childhood all too often squelch our “Asking faculty.” We grow up to be men and women, still eager for knowledge, but afraid and ashamed to ask in order to get it.

[…]

Every person possessing knowledge is more than willing to communicate what he knows to any serious, sincere person who asks. The question never makes the asker seem foolish or childish — rather, to ask is to command the respect of the other person who in the act of helping you is drawn closer to you, likes you better and will go out of his way on any future occasion to share his knowledge with you.

Ask! When you ask, you have to be humble. You have to admit you don’t know! But what’s so terrible about that? Everybody knows that no man knows everything, and to ask is merely to let the other know that you are honest about things pertaining to knowledge.

- DESIRE

You never learn much until you really want to learn. A million people have said: “Gee, I wish I were musical!” “If I only could do that!” or “How I wish I had a good education!” But they were only talking words — they didn’t mean it.

[…]

Desire is the foundation of all learning and you can only climb up the ladder of knowledge by desiring to learn.

[…]

If you don’t desire to learn you’re either a num-skull [sic] or a “know-it-all.” And the world wants nothing to do with either type of individual.

- GET IT FROM YOURSELF

You may be surprised to hear that you already know a great deal! It’s all inside you — it’s all there — you couldn’t live as long as you have and not be full of knowledge.

[…]

Most of your knowledge, however — and this is the great difference between non-education and education — is not in shape to be used, you haven’t it on the tip of your tongue. It’s hidden, buried away down inside of you — and because you can’t see it, you think it isn’t there.

Knowledge is knowledge only when it takes a shape, when it can be put into words, or reduced to a principle — and it’s now up to you to go to work on your own gold mine, to refine the crude ore.

- WALK AROUND IT

Any time you see something new or very special, if the thing is resting on the ground, as your examination and inspection proceeds, you find that you eventually walk around it. You desire to know the thing better by looking at it from all angles.

[…]

To acquire knowledge walk around the thing studied. The thing is not only what you touch, what you see; it has many other sides, many other conditions, many other relations which you cannot know until you study it form all angles.

The narrow mind stays rooted in one spot; the broad mind is free, inquiring, unprejudiced; it seeks to learn “both sides of the story.”

Don’t screen of from your own consciousness the bigger side of your work. Don’t be afraid you’ll harm yourself if you have to change a preconceived opinion. Have a free, broad, open mind! Be fair to the thing studied as well as to yourself. When it comes up for your examination, walk around it! The short trip will bring long knowledge.

- EXPERIMENT

The world honors the man who is eager to plant new seeds of study today so he may harvest a fresh crop of knowledge tomorrow. The world is sick of the man who is always harking back to the past and thinks everything wroth knowing has already been learned. … Respect the past, take what it offers, but don’t live in it.

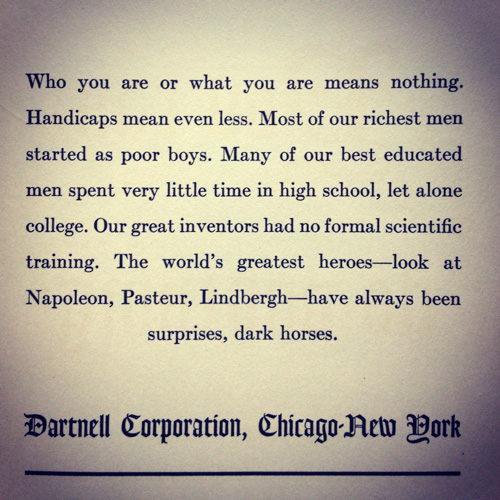

To learn, experiment! Try something new. See what happens. Lindbergh experimented when he flew the Atlantic. Pasteur experimented with bacteria and made cow’s milk safe for the human race. Franklin experimented with a kite and introduced electricity.

The greatest experiment is nearly always a solo. The individual, seeking to learn, tries something new but only tries it on himself. If he fails, he has hurt only himself. If he succeeds he has made a discovery many people can use. Experiment only with your own time, your own money, your own labor. That’s the honest, sincere type of experiment. It’s rich. The cheap experiment is to use other people’s money, other people’s destinies, other people’s bodies as if they were guinea pigs.

- TEACH

If you would have knowledge, knowledge sure and sound, teach. Teach your children, teach your associates, teach your friends. In the very act of teaching, you will learn far more than your best pupil.

[…]

Knowledge is relative; you possess it in degrees. You know more about reading, writing, and arithmetic than your young child. But teach that child at every opportunity; try to pass on to him all you know, and the very attempt will produce a great deal more knowledge inside your own brain.

- READ

From time immemorial it has been commonly understood that the best way to acquire knowledge was to read. That is not true. Reading is only one way to knowledge, and in the writer’s opinion, not the best way. But you can surely learn from reading if you read in the proper manner.

What you read is important, but not all important. How you read is the main consideration. For if you know how to read, there’s a world of education even in the newspapers, the magazines, on a single billboard or a stray advertising dodger.

Th secret of good reading is this: read critically!

Somebody wrote that stuff you’re reading. It was a definite individual, working with a pen, pencil or typewriter — the writing came from his mind and his only. If you were face to face with him and listening instead of reading, you would be a great deal more critical than the average reader is. Listening, you would weigh his personality, you would form some judgment about his truthfulness, his ability. But reading, you drop all judgment, and swallow his words whole — just as if the act printing the thing made it true!

[…]

If you must read in order to acquire knowledge, read critically. Believe nothing till it’s understood, till it’s clearly proven.

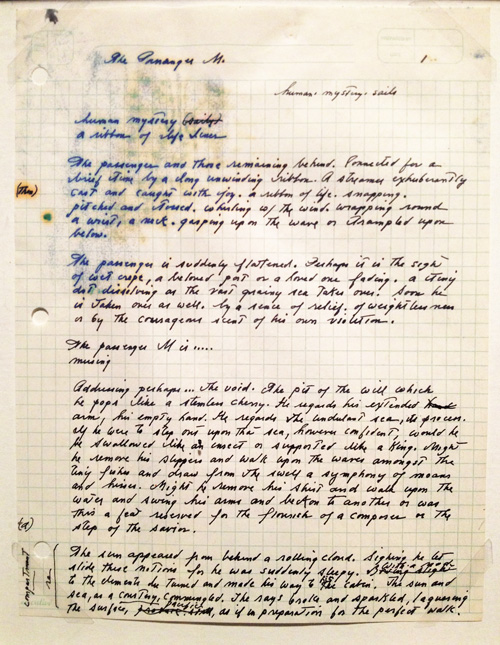

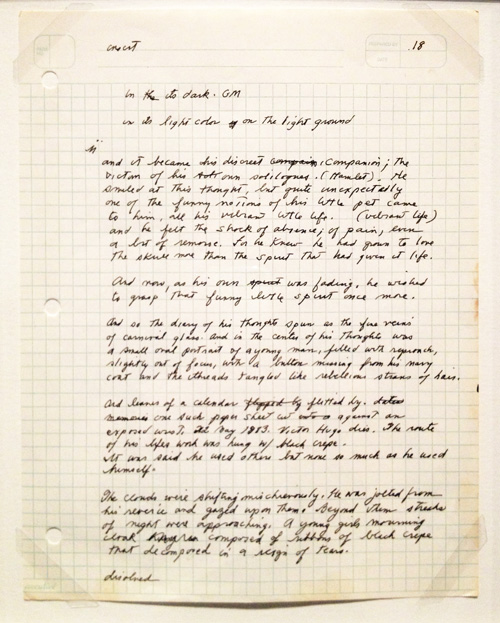

- WRITE

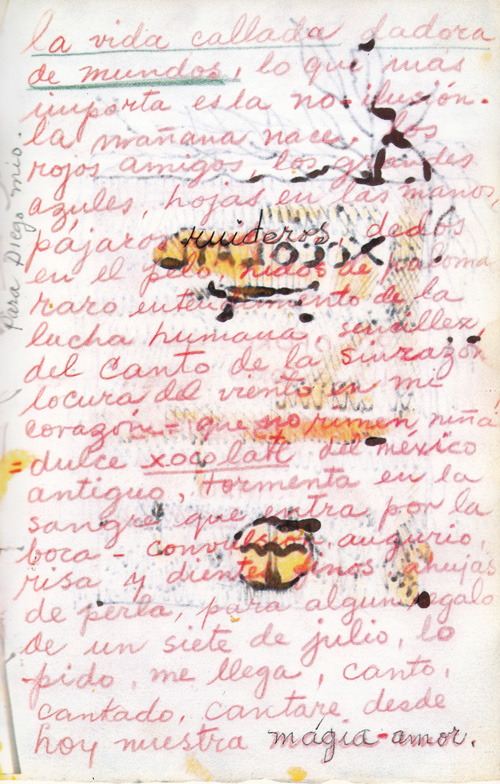

To know it — write it! If your’e writing to explain, you’re explaining it to yourself! If you’re writing to inspire, you’re inspiring yourself! If your’e writing to record, you’re recording it on your own memory. how often you have written something down in order to be sure you would have a record of it, only to find that you never needed the written record because you had learned it by heart!

[…]

The men of the best memories are those who make notes, who write things down. They just don’t write to remember, they write to learn. And because they DO learn by writing, they seldom need to consult their notes, they have brilliant, amazing memories. How different from the glib, slipshod individual who is too proud or too lazy to write, who trusts everything to memory, forgets so easily, and possesses so little real knowledge.

[…]

Write! Writing, to knowledge, is a certified check. You know what you know once you have written it down!

- LISTEN

You have a pair of ears — use them! When the other man talks, give him a chance. Pay attention. If you listen you may hear something useful to you. If you listen you may receive a warning that is worth following. If you listen, you may ear the respect of those whose respect you prize.

Pay attention to the person speaking. Contemplate the meaning of his words, the nature of his thoughts. Grasp and retain the truth.

Of all the ways to acquire knowledge, this way requires least effort on your part. You hardly have to do any work. You are bound to pick up information. It’s easy, it’s surefire.

- OBSERVE

Keep your eyes open. There are things happening, all around you, all the time. The scene of events is interesting, illuminating, full of news and meaning. It’s a great show — an impressive parade of things worth knowing. Admission is free — keep your eyes open.

[…]

There are only two kinds of experience: the experience of ourselves and the experience of others. Our own experience is slow, labored, costly, and often hard to bear. The experience of others is a ready-made set of directions on knowledge and life. Their experience is free; we need suffer none of their hardships; we may collect on all their good deeds. All we have to do is observe!

Observe! Especially the good man, the valorous deed. Observe the winner that you yourself may strive to follow that winning example and learn the scores of different means and devices that make success possible.

Observe! Observe the loser that you may escape his mistakes, aroid the pitfalls that dragged him down.

Observe the listless, indifferent, neutral people who do nothing, know nothing, are nothing. Observe them and then differ from them.

- PUT IN ORDER

Order is Heaven’s first law. And the only good knowledge is orderly knowledge! You must put your information and your thoughts in order before you can effectively handle your own knowledge. Otherwise you will jump around in conversation like a grasshopper, your arguments will be confused and distributed, your brain will be in a dizzy whirl all the time.

- DEFINE

A definition is a statement about a thing which includes everything the thing is and excludes everything it is not.

A definition of a chair must include every chair, whether it be kitchen chair, a high chair, a dentist’s chair, or the electric chair, It must exclude everything which isn’t a chair, even those things which come close, such as a stool, a bench, a sofa.

[…]

I am sorry to state that until you can so define chair or door (or a thousand other everyday familiar objects) you don’t really know what these things are. You have the ability to recognize them and describe them but you can’t tell what their nature is. You knowledge is not exact.

- REASON

Animals have knowledge. But only men can reason. The better you can reason the farther you separate yourself from animals.

The process by which you reason is known as logic. Logic teaches you how to derive a previously unknown truth from the facts already at hand. Logic teaches you how to be sure whether what you think is true is really true.

[…]

Logic is the supreme avenue to intellectual truth. Don’t ever despair of possessing a logical mind. You don’t have to study it for years, read books and digest a mountain of data. All you have to remember is one word — compare.

Compare all points in a proposition. Note the similarity — that tells you something new. NOte the difference — that tells you something new. Then take the new things you’ve found and check them against established laws or principles.

This is logic. This is reason. This is knowledge in its highest form.

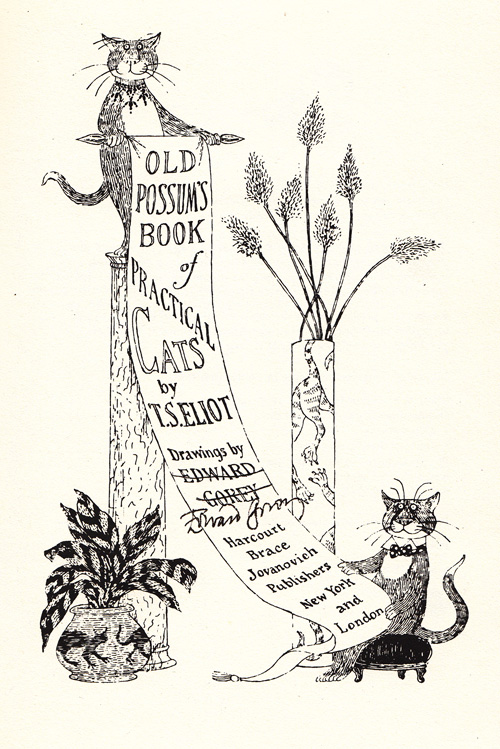

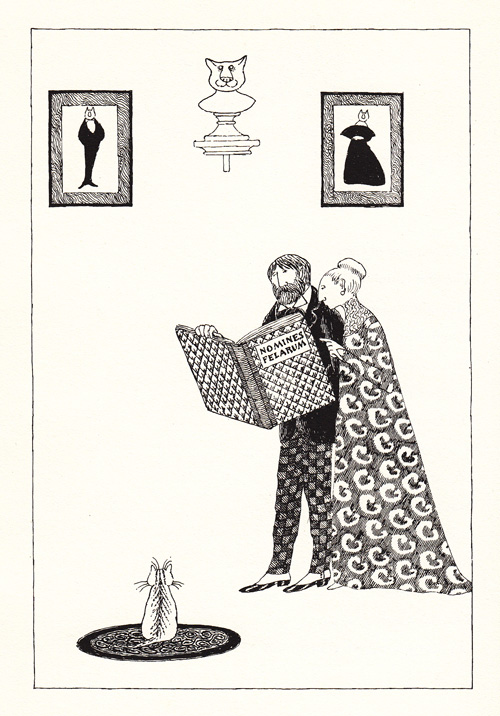

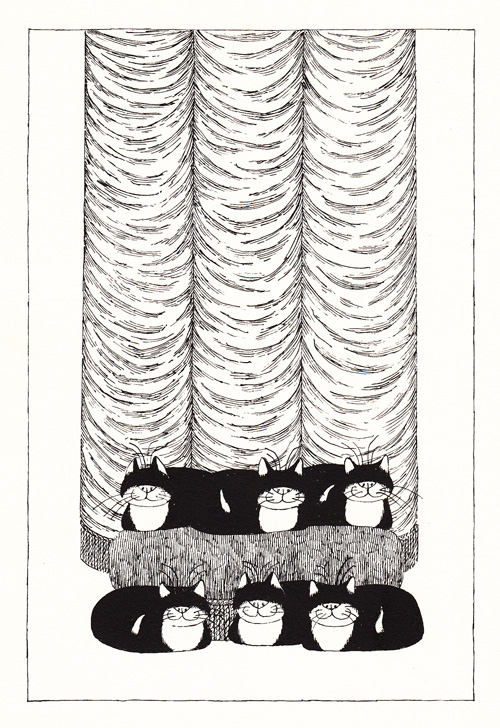

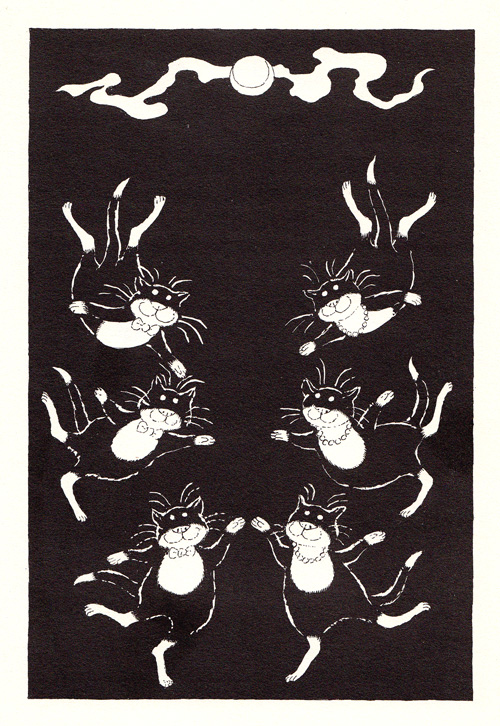

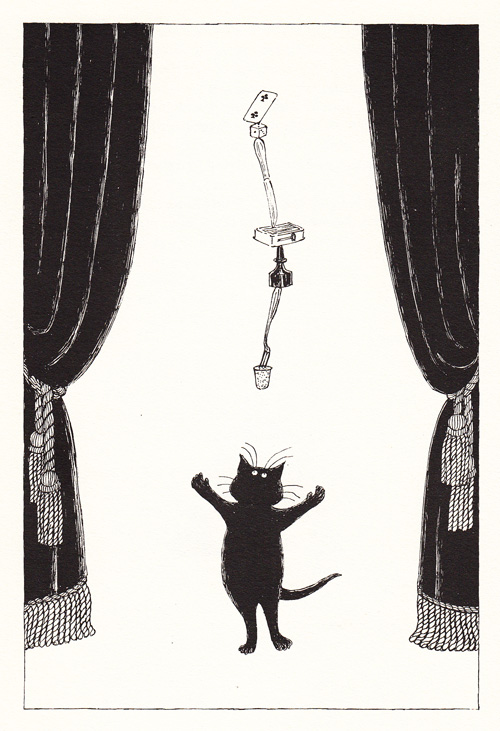

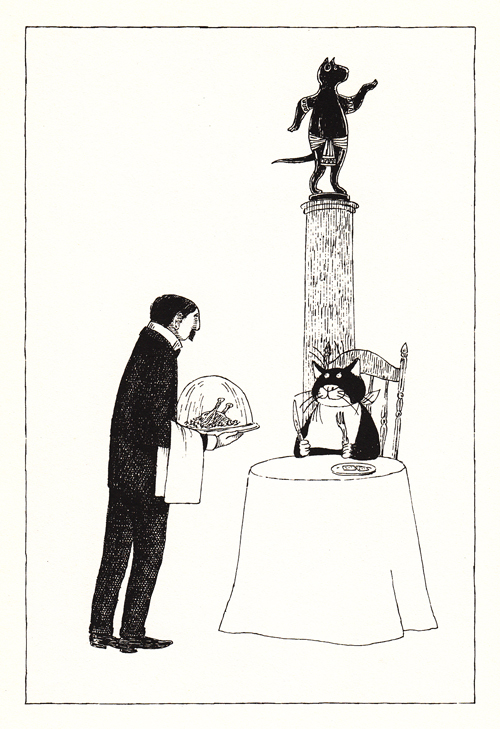

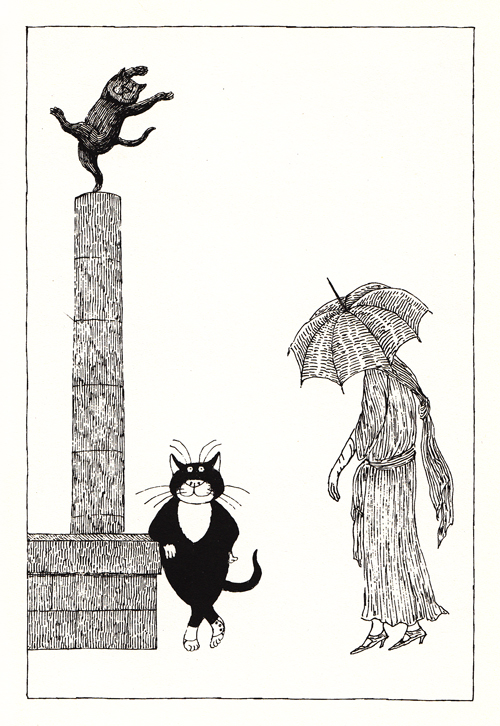

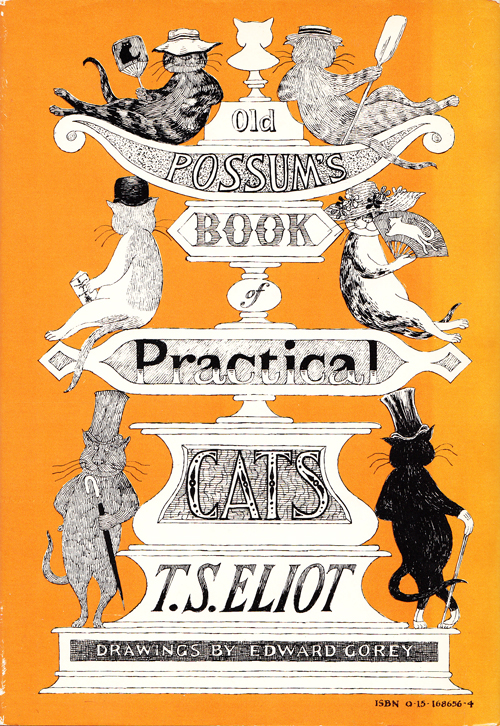

Until the wonderful Lost Cat: A True Story of Love, Desperation, and GPS Technology came out, the great Edward Gorey had the corner on feline art with his timeless illustrations for the 1982 edition of Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (public library) by T. S. Eliot, a documented cat-lover, who penned these whimsical verses about feline psychology and social order in a series of letters to his godchildren in the 1930s. The poems were first collected and published in 1939, adding Eliot to the ranks of other famous “adult” authors who wrote for children, and eventually became the basis for the famed Broadway musical Cats.

Until the wonderful Lost Cat: A True Story of Love, Desperation, and GPS Technology came out, the great Edward Gorey had the corner on feline art with his timeless illustrations for the 1982 edition of Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (public library) by T. S. Eliot, a documented cat-lover, who penned these whimsical verses about feline psychology and social order in a series of letters to his godchildren in the 1930s. The poems were first collected and published in 1939, adding Eliot to the ranks of other famous “adult” authors who wrote for children, and eventually became the basis for the famed Broadway musical Cats.

Isaac Asimov —

Isaac Asimov —